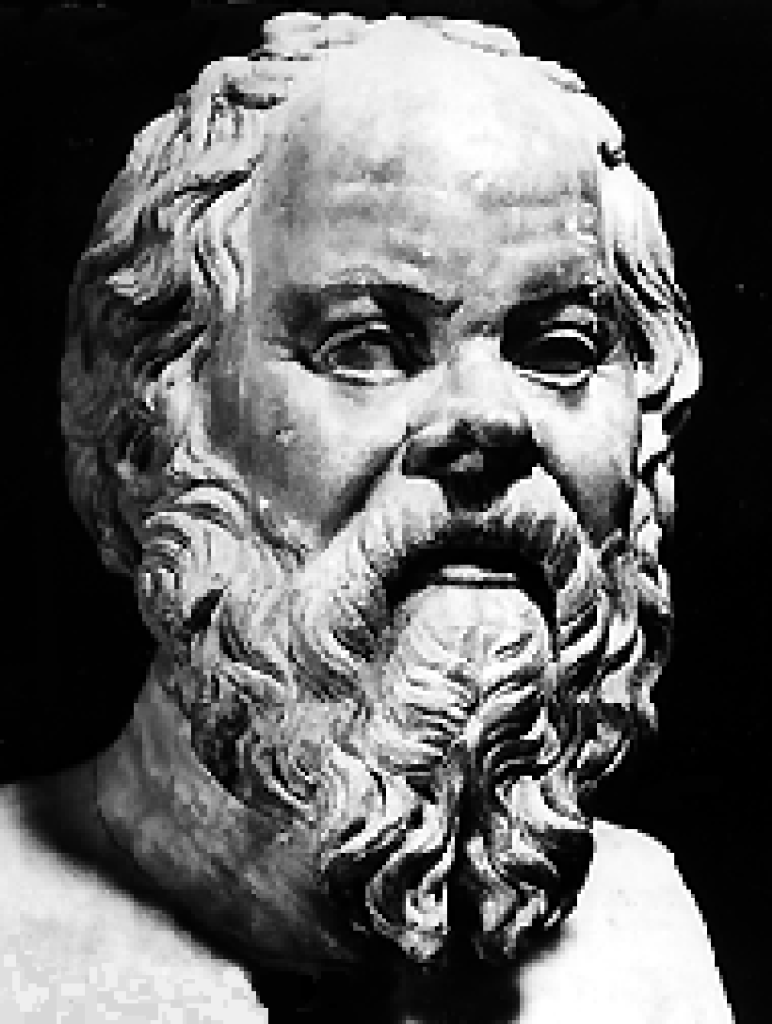

What is generally under-appreciated in the field of psychotherapy – perhaps particularly among clinical psychologists – is the fact that the Socratic Method (or Elenchus), the principal tool in the cognitive therapies for eliciting a patient’s unhelpful and erroneous beliefs, was born not of a concern for logical argument or for reason as such, but from something quite different; Socrates’ main concern was for the soul – not something which features very prominently in modern clinical psychology discourse.

Socrates would likely have been thrilled at the thought that, two-thousand-four-hundred years after his death, philosophers and psychologists alike are still using his name and ideas. As a thinker who turned away from the stars and the Heavens to understand the inner-life, modern psychological therapies would have appealed to him greatly as a form of self-enquiry and of healing. And though we perhaps more readily recognise Socrates in the practice of clinical psychology, it may be the case that his own dictum, ‘the unexamined life is not worth living’, traditionally believed to have been uttered by him at his trial for impiety and corruption, would have led him to a particular interest in psychoanalysis.

Maybe.

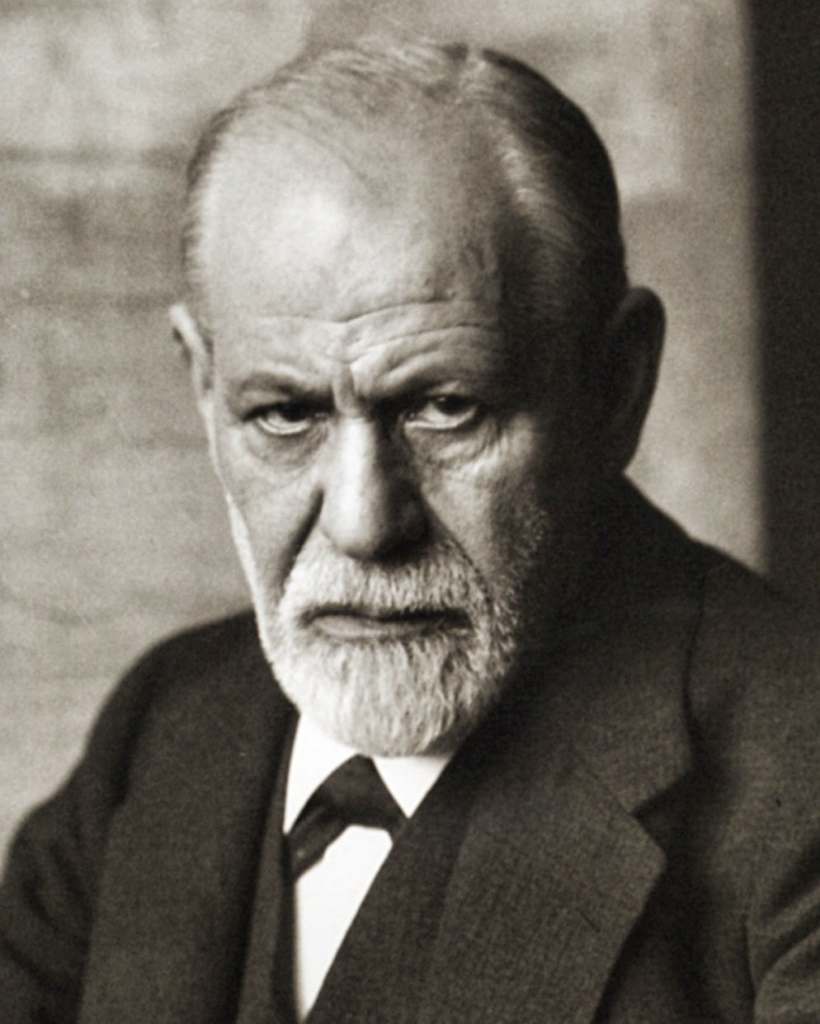

What we can in fact only guess at is what Socrates would have thought of Freud’s description of the inner-life of the soul as being populated by the gods: Psyche, Eros, Thanatos and by mythical hunters and kings such as Narcissus and Oedipus. Socrates was far from indifferent to the ancient gods: as Plato tells us, he was critical of Homeric references to their vices. (Socrates wanted his gods to be upstanding and virtuous so that everyone else might follow suit.) Might he therefore have felt that Freud had gone a step too far in his allegorical use of these celestial figures? Or maybe he would have been very open to the idea of the gods as qualities of the human soul as Freud understood them; of course, we cannot know. We can suppose, though, that Socrates would have struggled with the Freudian Id. The idea of something so virtueless, so atavistic and irrational at the root of human behaviour would likely not have appealed to him at all.

Yet, Socrates’ understanding of the mind was surprisingly quite similar to Freud’s in a number of ways. Essentially, both men believed that we have animal natures: a beast within. Where psychoanalysis lays its emphasis on the power of our instinctual drives, however, the Socratic view of mind assumes that certain kinds of knowledge create in us a defining sense of virtue and of ‘Good’.

Where Freud and Socrates possibly differ most significantly is in their respective legacies. Where psychoanalysis emphasises the opacity of the psyche, the quality of ‘depth’ therein, the use of Socratic Method in modern psychology assumes a more transparent, a more knowable quality to the mind.

The account given by Plato in his work, the Meno suggests – though somewhat ambiguously – that Socrates would have regarded his own elenctic method not only as a means to elicit the thoughts and beliefs of others, but as a means by which the soul can recollect innate knowledge, passed from reincarnation to reincarnation. In other words, Socrate believed – or may have believed – that what we have forgotten can be re-known, that is, re-cognised.

It is not unreasonable in my view to suggest that we should now think of Socrates more as a unifying figure, as having some relevance to different therapeutic modalities, rather than as a kind of trump card in the hands of clinical psychology. After all, he died in defence of the curious mind, of asking questions of the self. He believed, surely as do we all, in bringing people to an understanding of themselves. In this, like Freud, Socrates was undoubtedly very courageous.

Despite the distance in time between us, it is not surprising that Socrates has such a clean bill of health in modern psychology. His ideas and his ideals speak for themselves. As a man, he was of course fallible flesh and blood. A one-time courageous soldier from a turbulent and, at times, a warlike state, he was at least tolerant of the enslavement of ‘unjust’ enemies. Somewhat ironically, or so it seems to me, it is precisely because of his many references to antiquity that Freud is so often dismissed by psychologists and counsellors alike as, well, antiquated. Had the two men ever actually had the chance to meet, the lively question of who would have had the last word is for the consideration of far more learned minds than mine.

NB