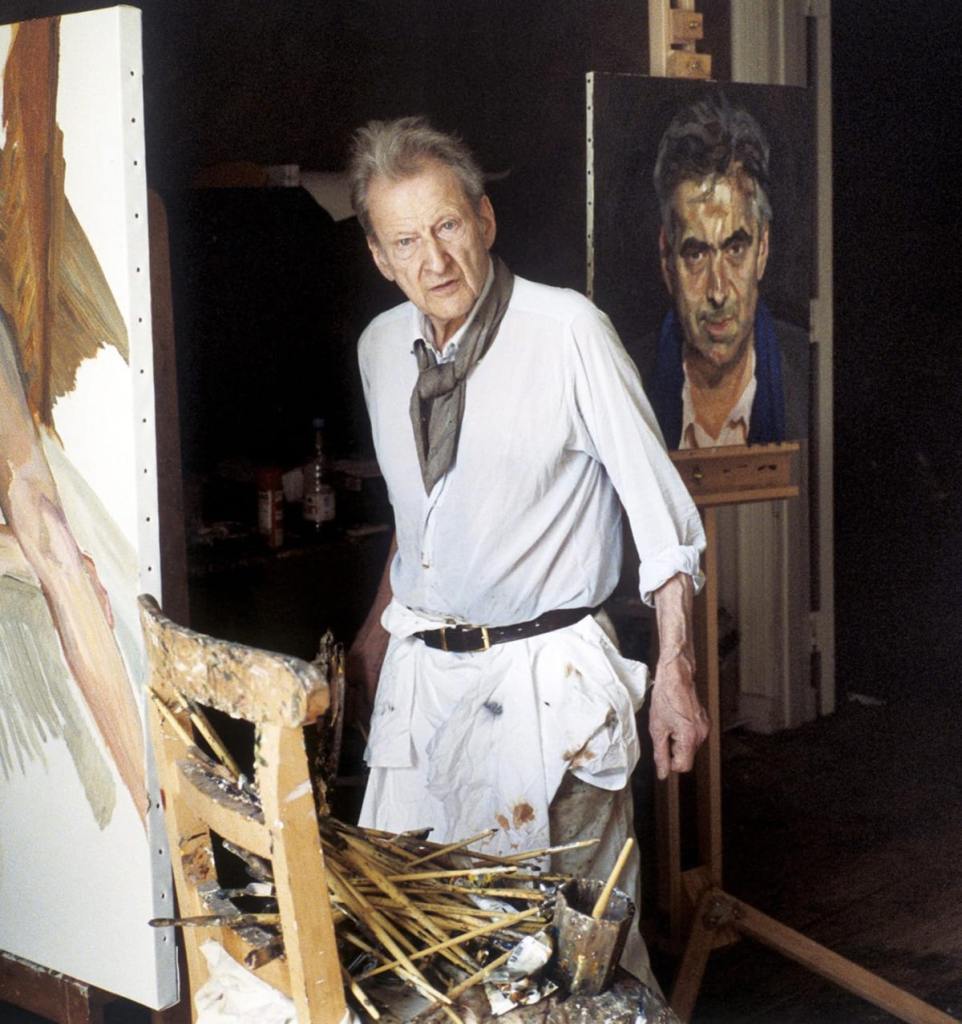

In a documentary film made about him by his friend and long-term assistant David Dawson, the artist Lucian Freud tells us that he had no great interest in his grandfather’s legacy beyond his work as a biologist. Such a view makes sense given (Lucian) Freud’s preoccupation with the object as it presents itself, as it were, rather than with a subject, with something that we might imagine has meaning beyond the surface of things. We may be interested in any one of Freud’s paintings and feel that we learn something about the artist. But the man himself would perhaps have agreed with the early twentieth century artist, Wyndham Lewis, who observed of himself that ‘the only thing that interests me is the shell’. It is more than simply a play on words to suggest that Freud’s representation of the naked human form undresses us; it strips away our pretensions, revealing the whole animal. We know just from looking at his portraits and self-portraits that the most real thing in the room for him is the body. Whether painting a person, a horse or a bird, nothing else matters.

And yet, despite his statement on film to the contrary, Freud was at least to some degree analytical in his approach to his craft. Painting is after all a language of sorts; every stoke of the brush communicates some form of judgement about how to represent this particular object in this particular way. We might reasonably ask, how is Freud looking? And, what elements of his own subjectivity as an artist do in fact inform his view of objective reality?

Ultimately, of course, we must ask the same questions of his grandfather too.

Recently, I watched a short YouTube film named Questioning Psychoanalysts , made by the Institute of Analysis, in which a psychologist, a psychotherapist and a neuroscientist put questions to a group of analysts, including training analyst and novelist Gregorio Kohon. The idea behind the film seems to be to explore the psychoanalytic approach to the mind and, assumedly, to promote a sense of its ongoing relevance to the modern world.

In response to a question about interpretation, Kohon recounts a hypothetical case in which a patient cuts his finger whilst slicing vegetables. The patient’s own associations concerning this relate to a forthcoming holiday, especially to the fact that his mother-in-law has been invited by his wife to come along. Kohon suggests that the act of self-cutting is a kind of unconscious attack, possibly on the man’s wife or, in fact, on the hated mother-in-law. It is suggested too that the attack represents the patient’s own feelings of impotence and of castration. This case exemplifies the fact that, as well as jokes and slips of the tongue, the analyst is also interested in what substitutes for language – in this case an accident – as an unconscious expression of a patient’s true feelings and motives.

In the film, emphasis is placed on the idea that meaning in the psychoanalytic relationship emerges little by little; analyst and patient work together for a better understanding of the patient’s experience. The question of how far an analysis is in fact a shared experience remains potent in the discussion; how well in reality does the idea of shared meanings sit with the fact that, after an accidental cut to a finger with a knife, the most real thing in the room for Kohon is an expression of murderous feelings by a man toward his mother-in-law? Kohon’s response is to point to the fact that psychoanalytic theory is very stimulating, very exciting, precisely because it includes the unconscious; it unapologetically speaks to the complexity of what the human psyche is. The analysts present agree that it is only psychoanalysis that can approach this complexity – through language, through experience, through the three to five times weekly, three to ten year, fifty pounds per session relationship. Simplification, collaboration, diagrammatic models illustrating a process of change and transparency in communication: for good reason, all these things exist outside what psychoanalysis is, not because the theory is overly complex but because any one life is so complex – Kohon speaks of one million-billion synapses in the brain – more complex than we can ever truly, fully understand.

But, what if it was just a cut? If this were true, we’d have to accept what some of us who have undergone a long psychoanalytic training might find it difficult to accept, that what we see is not truth or reality but a version of it. In other words, Kohon may actually be wrong in his assertion that psychoanalytic complexity mirrors the complexity of its subject. If we too look with different eyes, as it were, we may paint a different picture.